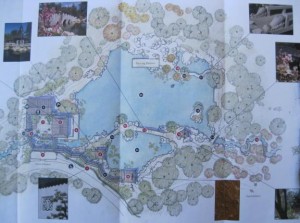

After visiting gardens in China we looked forward to visiting the Chinese garden at the Huntington. In preparation, I read the book published by the Huntington, Another World Lies Beyond, about the creation and construction of the garden and was impressed by the care with which the garden was designed and built. The garden was a bicultural effort and involved bringing materials as well as craftsmen from China. The Huntington Chinese garden is not a replication of any particular Chinese garden but draws from the tradition of the classical Chinese gardens such as those in Souzhou, China, with modifications introduced to accommodate both the differences in climate and the demands of building codes.

After visiting gardens in China we looked forward to visiting the Chinese garden at the Huntington. In preparation, I read the book published by the Huntington, Another World Lies Beyond, about the creation and construction of the garden and was impressed by the care with which the garden was designed and built. The garden was a bicultural effort and involved bringing materials as well as craftsmen from China. The Huntington Chinese garden is not a replication of any particular Chinese garden but draws from the tradition of the classical Chinese gardens such as those in Souzhou, China, with modifications introduced to accommodate both the differences in climate and the demands of building codes.

The garden’s name is Liu Fang Yuan, meaning the Garden of Flowing Fragrance, a name with both literal and symbolic meanings. Fang has a long history in Chinese lyric poetry and means fragrance, specifically of flowers, and is a metaphor of feminine beauty; Liu means flowing, but also lingering. The phrase liu-fang was used almost 2000 years ago by a poet to describe a goddess as she walked through a garden, and also pulls up images of scenes created by the famous Ming landscape artist, Li Liufang. In a similar fashion, all the structures in the garden itself have names with several layers of meaning that add to the enjoyment of the garden.

The garden’s name is Liu Fang Yuan, meaning the Garden of Flowing Fragrance, a name with both literal and symbolic meanings. Fang has a long history in Chinese lyric poetry and means fragrance, specifically of flowers, and is a metaphor of feminine beauty; Liu means flowing, but also lingering. The phrase liu-fang was used almost 2000 years ago by a poet to describe a goddess as she walked through a garden, and also pulls up images of scenes created by the famous Ming landscape artist, Li Liufang. In a similar fashion, all the structures in the garden itself have names with several layers of meaning that add to the enjoyment of the garden.

The entrance to the garden immediately tells you that you have arrived at the Chinese garden.

A serpentine wall very reminiscent of the wall in the Shanghai garden, runs along one side of the garden.

We walked to the end of the wall hoping to see a dragon head like the one in the Shanghai garden;

But, alas, there was none. Too bad, it’s a great feature. Perhaps in the future.

Just inside, a carved stone introduces you to the garden. The Chinese characters on the stone evoke associations with Daoism and a literary composition that tells the story of fisherman who accidentally finds a hidden world inside a little hillside cave.

Inside the garden wall we can enjoy the elements of a typical Chinese garden; water, architecture, rocks, and plants.

The Lake of Reflected Fragrance is the centerpiece of the garden, its name echoing the name of the garden.

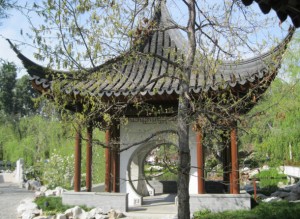

Numerous pavilions are nestled around the lake. Terrace of the Jade Mirror has circular doors on all four sides, suggesting the moon. In literature and poetry a jade mirror is a metaphor of the moon and terrace suggests a holder, so the name of the pavilion literally means “jade-mirror set”, a symbol of an engagement gift in literature.

The name Love for the Lotus Pavilion takes its name from an essay written by a scholar in the 11th century who loved the lotus more than any other flower because its pure and perfect flowers come up from the muddy lake bottom and spread their fragrance. Unfortunately, the lotuses were not blooming in mid March when we visited.

Eight carved wood panels of Suzhou gardens decorate the inside of the Love for the Lotus Pavilion.

The Pavilion of Three Friends celebrates three plants, pine, bamboo, and plum that are considered symbols of unity, courage, and tenacity in Chinese literature. The pine and bamboo stay green all winter, while the plum produces its flowers in early spring before the last frost.

The Freshwater Pavilion is the teashop. The Chinese words for the pavilion literally mean “living water” or “water with life” and refer to a poem on tea in which the author scoops up “living water” from a deep river to make tea.

Camellias are highly esteemed in China and since they belong to the same genus as the tea plant, are used as a decorative motif for this pavilion as well as the Hall of the Jade Camilla.

Hall of the Jade Camellia takes its name from the residence of a 16th century Chinese playwright associated with the white camellia, loved as a symbol of purity and nobility.

Outside the Hall of the Jade Camellia, the Terrace that Invites the Mountain gives you an view of the lake with the San Gabriel Mountains in the background (only slightly visible in the mist.) Borrowing distant scenery is common in the gardens of China.

The Plantain Court connects the Hall of the Jade Camellia with the Freshwater Pavilion.

The plantains, or bananas, for which the court was named, were still dormant when we visited in mid-March, but the moon gate in the court was beautiful. In Chinese art and literature, banana plants are associated with the sound of raindrops on broad leaves, creating a quiet and almost melancholy atmosphere.

The Studio of Pure Scents lies on one side of the Plantain Cour with straight and picturesque corridors reaching out on both sides.

The wall of the corridor is pierced by leaky windows to give a glimpse inside.

The Corridor of Water and Clouds runs from the Hall of the Jade Camellia to the Love for the Lotus Pavilion. Its zig zag path recall the ever changing characteristic of nature.

Numerous bridges add their charm to the scene. The Bridge of the Verdant Mist leads to the Isle of Alighting Geese.

The Isle of Alighting Geese honors the legendary romantic devotion and loyalty of migratory wild geese and their ability to soar as they fly.

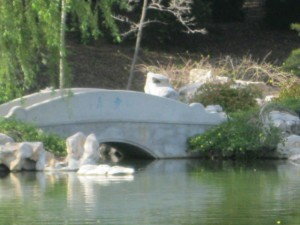

The Jade Ribbon Bridge leads from the Isle of Alighting Geese back to the main shore. Note the reflection of the bridge in the water.

The proportions of the bridge are heavier and taller than similar bridges in China and this is due to the necessity of providing guardrail-height handrails on bridges that arch high over water.

The diminutive Listening to the Pines bridge stands in a grove of pines.

The Bridge of the Joy of Fish leads from the lake edge to the Mandarin Ducks Island.

The name of the bridge recalls a famous discussion in a Daoist text about how a person could know what fish enjoy.

The Mandarin Ducks Island is tiny but its name has a significant meaning; Mandarin ducks are believed to mate for life and so symbolize a living and harmonious marriage.

The Bridge of Strolling in the Moonlight leads from mandarin Duck Island to the edge of the lake and evokes a poem about two friends enjoying a moonlit night together.

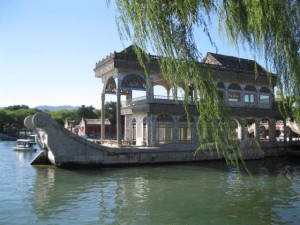

A concrete structure near by is called a viewing platform.

It’s shape bears a striking resemblance to the marble boat in the Summer Palace in Beijing and perhaps future plans intend to develop it more.

Rocks are an important part of any Chinese garden. They represent the mountains and energy, and are often used like European gardens use statuary. The rocks in Liu Fang Yuan are from Lake Tai in China, an area renowned for its spectacular rocks.

More often, the rock are combined with vegetation as in the Cascade of Resonant Bamboo.

The plants in the garden were just beginning to bloom in mid-March when we visited and many are young, as you would expect in a newly created garden. The beauty of the garden, however, is still evident and well worth a visit in any season.

The garden is not complete and plans are in the making to expand it and add more features. I can hardly wait!